This worker clearly had an alcohol problem. But did her employer do what was required to help her?

When Diane Ames was hired by Home Depot she was given a copy of the company’s code of conduct.

It said an employee can be fired the first time he/she tests positive for alcohol based on a blood test.

A few years later Ames told the store manager she had an alcohol problem and needed help through the company’s employee assistance program (EAP).

Because her alcohol problem had not affected her work, Ames wasn’t terminated and was put on paid leave until she received a treatment plan, a return-to-work authorization and passed a return-to-work drug test.

At the same time, Home Depot agreed to enroll Ames in its EAP as long as she signed an agreement stating she would be subject to periodic drug and/or alcohol testing during the remainder of her employment. If she failed a test, she’d be terminated.

She signed.

Problems begin to mount

A month later, she obtained an authorization and returned to work. She also submitted a note from her primary care physician stating that she had been referred to a social worker for counseling and a psychiatrist to help manage her medications.

Shortly after returning to work, Ames was arrested for driving under the influence.

Her EAP case worker told Ames she had to schedule an appointment to be evaluated at a treatment facility.

Following that incident, Ames arrived at work smelling of alcohol and slurring her words. She was then driven to a testing facility where her blood work showed she was under the influence of alcohol.

Home Depot responded by terminating her.

Ames then turned around and sued Home Depot, claiming the company violated her right to take leave under the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and for retaliating against her for asking for leave.

Ames claimed she gave Home Depot proper notice of her need for FMLA leave. Do you think she had a case?

The verdict

According to the court, she didn’t.

The note from her physician stating she had been referred to a social worker and a psychiatrist did not give the company adequate notice of her need for leave, the court said.

In addition, the FMLA couldn’t protect Ames because she failed to show she had a serious health condition.

Substance abuse can qualify as a serious health condition under the FMLA if it involves “inpatient care” or “continuing treatment” by a healthcare provider.

At no point before her termination did Ames go into inpatient care.

And continuing treatment must involve a period of incapacity of more than three days — a requirement Ames’ treatment also failed to satisfy.

As for her retaliation claim, the court said she was fired for violating Home Depot’s code of conduct, not for anything tied to FMLA leave.

The fact that Ames reported to work under the influence of alcohol was a failure to meet Home Depot’s legitimate job expectations, and the company was not required to accommodate Ames’ alcoholism by overlooking violations of its workplace rules, the court said.

In addition, the court said Home Depot was more than fair when it didn’t terminate her — and instead allowed her to take personal leave without penalty — after she continued to have alcohol-related problems.

Cite: Ames v. Home Depot

Our HR editorials undergo rigorous vetting by HR and legal experts, ensuring accuracy and compliance with relevant laws. With over two decades of combined experience in Human Resources thought leadership, our editorial team offers profound insights and practical solutions to real-world HR challenges. This expertise not only enhances the credibility of our content but also makes HRMorning a dependable resource.

For more information, read our editorial policy.

Why do we need your credit card for a free trial?

We ask for your credit card to allow your subscription to continue should you decide to keep your membership beyond the free trial period. This prevents any interruption of content access.

Your card will not be charged at any point during your 21 day free trial

and you may cancel at any time during your free trial.

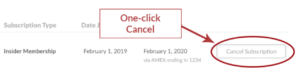

During your free trial, you can cancel at any time with a single click on your “Account” page. It’s that easy.