Here’s proof that there’s no bigger pain in the butt for employers than the Family and Medical Leave Act.

The most recent horror story comes out of Tennessee, where a receptionist for a local newspaper was fired for excessive absenteeism.

The receptionist had missed several consecutive days of work, saying her absence was due to illness — first her young son’s, then her own.

Her supervisor informed her that she should fill out a short-term disability form (which also served as a FMLA leave form) “to see if she qualified for anything” in the area of medical leave.

She visited a physician, who in turn provided a medical certification form — but the doctor didn’t indicate that she was suffering from a medical condition that’d trigger eligibility for leave.

Indeed, the certification said just the opposite. The doctor’s opinion was that the woman should have been able to return to work the day after the appointment.

The woman continued to stay out of work. The employer double-checked the certification with the physician, who stood behind the original diagnosis.

The woman was fired.

New certification

Now things get complicated. The woman provided another medical certification form, this one from a nurse practitioner in the same practice as the woman’s previous doctor.

The nurse practitioner said the receptionist wouldn’t be able to return to work for several months.

After the company stuck to its termination decision, the woman sued, saying the employer had interfered with her FMLA rights.

The federal district court sided with the company, saying it was entitled to fire the employee when it received the “negative certification” from the doctor.

The company wasn’t obligated to “delay its termination decision until receipt of the second, unanticipated medical certification,” the judge wrote.

Not good enough, says appeals court

That common-sense approach to the case was turned on its ear by the federal appeals court.

Why? Timing.

FMLA gives employees 15 days to provide certification of a serious medical condition.

The decision to fire the receptionist was made 11 days into the process — 11 days after the company told her she needed to provide the paperwork.

And guess what? The nurse practitioner’s certification — the one that said the woman would need several months off — was received on the 15th day.

The other problem: The oral instructions from the woman’s supervisor were too vague. She wasn’t told specifically about certification requirements or the 15-day deadline.

So the appeals court came down on the side of the employee. The case now goes to trial, or gets settled out of court.

Got your crystal ball?

This case is a maddening example of how small oversights can trump common-sense decisions in FMLA cases.

The part of the decision that’s hardest to swallow: It appears the court is asking the employer to read the mind of the employee — in other words, somehow foresee that the second certification was forthcoming.

The company had received — and double-checked — official paperwork that indicated the employee wasn’t eligible for leave. And it made a reasonable business decision based on the information it had in hand.

Cite: Branham v. Gannett Satellite Information Network. For a look at the full court decision, go here.

Our HR editorials undergo rigorous vetting by HR and legal experts, ensuring accuracy and compliance with relevant laws. With over two decades of combined experience in Human Resources thought leadership, our editorial team offers profound insights and practical solutions to real-world HR challenges. This expertise not only enhances the credibility of our content but also makes HRMorning a dependable resource.

For more information, read our editorial policy.

Why do we need your credit card for a free trial?

We ask for your credit card to allow your subscription to continue should you decide to keep your membership beyond the free trial period. This prevents any interruption of content access.

Your card will not be charged at any point during your 21 day free trial

and you may cancel at any time during your free trial.

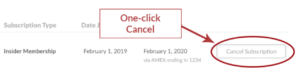

During your free trial, you can cancel at any time with a single click on your “Account” page. It’s that easy.