Sometimes, no matter how generous you are with leave benefits, some employees still won’t be satisfied. The good news: You can beat them in court.

Case in point: Jason Hearst was injured in a non-work-related car accident. As a result of his injuries, he requested a leave of absence from his employer, Progressive Foam Technologies (PFT). He said needed off from Jan. 3, 2007 to Feb. 5, 2007.

Even though Hearst had been employed at PFT for fewer than 10 months, PFT granted him leave under the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and told him it would count against his leave entitlement of 12 weeks.

Leave dragged on

Over a period of several months, Hearst and his physician submitted numerous requests to extend his leave.

March 15, 2007 marked Hearst’s one-year anniversary at PFT — and the date he would’ve ordinarily have become eligible for 12 weeks of FMLA leave.

On March 16, 2007, PFT sent Hearst a letter explaining that his 12-weeks of FMLA leave would be exhausted on March 28, and that it would extend his leave for an additional 30 days from that date.

Hearst then submitted a return-to-work date of May 1. But when he failed to report to work or contact the company by that date, he was terminated.

After his termination, Hearst’s physician provided a letter explaining he couldn’t return to work for at least several more months.

Regardless, his termination stood.

FMLA lawsuit filed

Hearst responded by suing the company, claiming it violated his FMLA rights.

His argument: May 1, the date of his termination, was only seven weeks after he should’ve initially become eligible for FMLA leave. So he should’ve still had five weeks of eligibility left at the time of his termination.

But the court didn’t bite. Courts have been fairly consistent about not punishing employers who go above and beyond the requirements of the FMLA — and this case was no different.

PFT could’ve denied his initial request, but it granted him FMLA leave. It also could’ve only given him 12 weeks, but it extended his leave (he was on leave for 16 weeks).

The court ruled Hearst failed to demonstrate that he had been prejudiced by the firing, a requirement for a company to be found in violation of the FMLA.

In addition, the court said Hearst showed no proof that he would’ve been able to return to work after a 12-week period from either Jan. 3 (when he initially went on leave) or March 15 (when he should’ve become eligible).

Cite: Hearst v. Progressive Foam Technologies, Inc.

Our HR editorials undergo rigorous vetting by HR and legal experts, ensuring accuracy and compliance with relevant laws. With over two decades of combined experience in Human Resources thought leadership, our editorial team offers profound insights and practical solutions to real-world HR challenges. This expertise not only enhances the credibility of our content but also makes HRMorning a dependable resource.

For more information, read our editorial policy.

Why do we need your credit card for a free trial?

We ask for your credit card to allow your subscription to continue should you decide to keep your membership beyond the free trial period. This prevents any interruption of content access.

Your card will not be charged at any point during your 21 day free trial

and you may cancel at any time during your free trial.

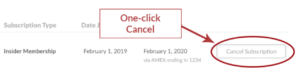

During your free trial, you can cancel at any time with a single click on your “Account” page. It’s that easy.