Click to jump ahead:

- What is the EEOC?

- EEOC Laws

- Federally Protected Classes

- Handling Discrimination Complaints

- How to Prevent Harassment in the Workplace

What is the EEOC?

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, more commonly referred to as the EEOC, is a federal agency that is authorized to enforce and interpret certain federal laws prohibiting employment discrimination against federally protected classes. The EEOC’s authority expands across the entire spectrum of the employment relationship. It covers situations involving hiring all the way through to issues involving separation from employment.

Promotions, workplace harassment, wages, training and benefits and retaliation are just some of the specific areas the EEOC has the authority to address.

The EEOC doesn’t always have the last word on specific employment issues; in fact, courts are free to reject EEOC guidance and interpretations. But that’s not what usually happens. Instead, courts tend to defer to the agency as sort of a subject-matter expert with respect to how federal anti-discrimination employment laws should be interpreted and applied.

A key takeaway from this fact: Knowing the EEOC’s position on a particular issue, as expressed through its guidance or enforcement activities, is a very important step covered employers should take to remain EEOC compliant.

Speaking of covered employers, most employers with at least 15 employees have to comply with the federal laws that the EEOC handles. (An exception applies with respect to the federal law banning age discrimination, which bumps the minimum number up to 20.)

In most instances, employment agencies and labor unions are also covered.

Employees who believe they have been discriminated against in violation of a law enforced by the EEOC can file an administrative charge of discrimination with the agency. The EEOC proceeds by investigating the charge and trying to resolve it without going to court.

If its investigation results in a finding that there has been unlawful discrimination, it tries to negotiate a settlement with the offending employer. If that doesn’t work, it can go ahead and file a lawsuit on the complaining employee’s behalf. But the agency’s resources are limited, and that happens in only a very small percentage of cases.

If the agency’s investigation results in a finding that the employer did nothing wrong, the complaining party can still choose to go to court without the EEOC’s help, subject to certain prescribed time limitations.

For an example of how this works in practice, click here.

The EEOC does much more than just investigate discrimination charges. It also tries to prevent employment discrimination via a number of outreach, technical assistance and education programs.

In addition, it helps federal agencies comply with equal employment opportunity requirements, and it periodically issues detailed guidance concerning specific discrimination-related employment law issues.

It also issues regulations regarding the laws it is authorized to enforce.

The agency has its headquarters in Washington, D.C., and it operates 53 offices nationwide.

EEOC Laws

The EEOC is authorized to interpret and enforce only certain specific federal laws. Essentially, employment discrimination is its domain. Here are the specific federal laws it enforces and what those laws say.

Title VII

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, more commonly referred to simply as Title VII, is a federal law banning employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin or sex. Remember that this law covers the entire employment process, from application through separation from employment.

Importantly, it also bans retaliation. More specifically, it prohibits covered employers from retaliating against a person because the person has filed a discrimination charge, complained about discrimination, or participated in an investigation or lawsuit.

Under Title VII, covered employers must accommodate the sincerely held religious beliefs of applicants and employees unless doing so would impose an undue hardship on the employer’s operations.

Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination encompasses a ban on sexual harassment in the workplace. In other words, under Title VII sexual harassment is a form of prohibited sex discrimination.

Physical or verbal conduct of a sexual nature is unlawful under Title VII when it negatively affects the victim’s employment, interferes unreasonably with work performance, or creates a hostile working environment. Under Title VII, the harasser can be a man or a woman, and the victim and the harasser can be of the same sex.

Here’s a fact that may come as a surprise: The victim does not have to be the direct target of the harassment. Instead, it can also be another employee who is also negatively affected by the harassing behavior.

For some important and enlightening EEOC stats about harassment in the workplace, click here.

Pregnancy Discrimination Act

The Pregnancy Discrimination was passed in 1978. It amended Title VII to specifically ban discrimination on the basis of pregnancy.

Under the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, covered employers cannot discriminate against women based on pregnancy, childbirth, or a medical condition that is related to either.

Like Title VII, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act prohibits employers from engaging in unlawful retaliation. Employers cannot retaliate against a person because the person complained of pregnancy discrimination, filed a discrimination charge, or participated in an investigation or lawsuit.

Equal Pay Act

The Equal Pay Act, or EPA, requires covered employers to provide equal pay to men and women who perform equal work in the same workplace.

The jobs don’t have to be identical; instead, the question is whether they are substantially equal. If they are, equal pay is required.

The law doesn’t address salary only. It covers all forms of pay, including things like overtime, bonuses, stock options and profit-sharing.

The EPA bans retaliation against those who have complained of discrimination, filed a discrimination charge, or participated in a discrimination lawsuit or investigation.

Age Discrimination in Employment Act

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act, or ADEA, prohibits covered employers from discriminating against individuals who are 40 years of age or older. The law applies to applicants as well as employees.

What if a covered employer favors an older employee over a younger one, and both employees are over the age of 40? This doesn’t violate the ADEA, according to the EEOC.

The person who discriminates does not have to be younger than 40 to trigger the ADEA’s protections, the agency adds. In other words, for example, an over-40 supervisor can violate the ADEA by discriminating against an over-40 employee.

The statute bars discrimination with respect to all terms and conditions of employment.

It also prohibits age-based harassment. Although isolated offhand comments relating to age probably won’t be enough to violate the law, employers may be on the hook if the harassment either creates a hostile or offensive work environment or leads to an adverse job action such as a demotion or termination from employment.

File this one under the “you may be surprised to learn” category: The harasser doesn’t have to be someone who works for the employer. Instead, it can be a client or customer.

Example: A 60-year-old salesman complains to his manager that a customer keeps telling him that he’s too old for the job and that he should retire. The manager tells the salesman that the company can’t afford to lose the account and that there’s nothing he can do. In this example, the employer may be liable under the ADEA for the harassment.

Americans with Disabilities Act

Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act, more commonly referred to as the ADA, prohibits covered employers from discriminating against qualified applicants and employees on the basis of disability.

A “disability” is a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits at least one major life activity, such as breathing, seeing, sleeping and walking. It also includes a record or past history or such an impairment as well as being regarded as having such an impairment.

The law applies to all aspects of the employment relationship, including hiring, firing, compensation, benefits, and all other terms and conditions of employment.

To win an ADA claim, an individual has to do more than show he has a disability; he must also show that he is qualified for the position that he seeks or holds.

A fundamental concept of Title I is that employers are required to make “reasonable accommodations” to help qualified individuals with disabilities do their jobs, subject to the limitation that employers need not make accommodations that would result in what the law calls an “undue hardship” for the employer.

Employers have to understand that the ADA thus goes far beyond merely requiring evenhanded treatment of people with disabilities. Instead, they must take affirmative steps to do things for people with disabilities that they need not do for people without disabilities, such as providing a sign-language interpreter for a deaf applicant during a job interview or providing regularly scheduled breaks to an employee with diabetes so that he can monitor his blood sugar and insulin levels. This is an absolutely critical point for employers to keep in mind.

Another good example of a form of reasonable accommodation is a leave of absence. When does leave become unreasonable? Click here to find out.

The ADA has some rules about medical examinations and inquiries. Think of it this way: One rule applies to applicants who have not been offered a position; a second rule applies to people who have been offered a position but have not yet started working; and a third applies to current employees.

Here’s how it shakes out.

Job applicants cannot be asked about the existence, nature or severity of a disability, although they can be asked whether they can perform job functions.

Once an offer is made, the offer can be made contingent on the results of a medical exam – as long as an exam is required for all new employees in similar jobs.

Finally, medical exams can be required for existing workers only if the exams are related to the job and are consistent with the employer’s legitimate business needs.

The ADA doesn’t protect people who use drugs illegally. This includes use of illegal drugs, such as crack cocaine, and illegal use of otherwise legal drugs, such as prescription pain medications.

A final word on the ADA’s employment requirements: Employers may not retaliate against an individual for opposing discriminatory employment practices or for filing a discrimination charge or participating in an investigation, lawsuit or other proceeding relating to the ADA.

Federally Protected Classes

The laws that the EEOC enforces apply to what are known as “protected classes” of individuals. Employers need to keep in mind that every single applicant and employee is a member of at least one of these protected classes. The classes correspond to the laws that create the protections.

Of course, the fact that an applicant or employee is “protected” does not mean that no adverse action can ever be taken against him. But employers can’t take adverse action against an employee based solely on the fact that he is a member of protected class.

Here are the protected classes created by federal laws barring employment discrimination.

Title VII created the protected classes of race, color, religion, national origin and sex.

These may sound pretty straightforward, but a couple of them are a bit more involved than they may seem to be.

Discrimination based on national origin, for example, includes bias based on the fact that someone is from a particular part of the world or country; because of ethnicity or an accent; or because they look like they are from a certain ethnic background.

Color definitely overlaps with race, but they aren’t the same thing. That means color discrimination can happen between two people of the same race. The EEOC defines “color” discrimination quite literally: The agency says it refers to skin pigmentation, complexion, or skin tone or shade.

It’s a mistake to assume that the protected class of religion encompasses only those who are part of traditional organized religions. The EEOC’s view is that the class also includes others who have “sincerely held religious, ethical or moral beliefs.”

Exactly what is meant by “sex” discrimination has been a hotly debated issue. Some say the class is meant to refer to one’s physical sex at birth as determined by sexual organs. But the EEOC says it’s much broader than that. The agency’s position is that unlawful sex discrimination under Title VII includes discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Under the ADEA, the answer of who is protected is much clearer: People who are at least 40 years old are members of the protected class.

The ADA creates the federally protected class of people with disabilities. Under the statute, a “disability” is a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits at least one major life activity, such as breathing, seeing, sleeping and walking. It also includes a record or past history or such an impairment as well as being regarded as having such an impairment.

The term “substantially limits” is construed broadly. Except for ordinary eyeglasses or contact lenses, the determination of whether a person is substantially limited in a major life activity is to be made without reference to the ameliorative effects of mitigating measures like medication.

Pregnancy is another protected class. Under the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, covered employers cannot discriminate against women based on pregnancy, childbirth, or a medical condition that is related to either.

Record-Keeping Requirements

The EEOC has issued regulations that require covered employers to hold on to personnel or employment records for a period of one year. When a worker is let go, his records are to be kept for a year from the termination date.

The ADEA requires employers to keep payroll records for a period of three years. Employee benefit plans as well as written seniority or merit systems are to be kept while the plan or system is in effect and for at least a year after termination.

Records that explain why different wages are paid to employees of opposite sexes in the same establishment are to be kept for at least two years.

EEO-1 Form

The EEOC collects information about employer workforces from employers that have 100 or more employees. Lower thresholds are applicable to federal contractors. Employers report this information annually using the EEO-1 Form.

Information relating to race/ethnicity, gender and job category is used to create a compliance survey.

The provision of the data by covered employers is not voluntary. Instead, the data must be provided.

The agency uses the information that is collected in the reports for a variety of purposes, including enforcement and research.

Here’s some information about the filing requirements for 2019.

Handling Discrimination Complaints

When an employee presents an employer with an internal complaint of discrimination or harassment, responding promptly and effectively is essential to avoiding legal liability. Here’s a general roadmap that employers should follow to stay EEOC compliant.

It should go without saying that the employer must take the complaint seriously and not jump to conclusions about whether it has merit. Employers need to keep an open mind about what happened and quickly proceed to conduct an objective, prompt and thorough investigation into whether any EEOC laws have been violated.

Promptness and thoroughness with respect to the investigation are key.

Employers should make sure to show empathy for the accuser, especially in cases involving alleged harassment on the basis of sex or some other protected characteristic, such as disability or age. Showing respect and compassion can greatly assist in achieving a swift and smooth resolution.

In harassment cases, it’s best for employers to speak directly to the accuser first. Then they should talk separately to the accused before following up with direct talks with any witnesses to the alleged harassment.

Employers should make sure to document, document, and then document some more. Every part of the investigation, from beginning to end, should be carefully documented in writing. It’s a good idea for the internal investigator to take notes contemporaneously during face-to-face interviews.

Details regarding the complaint should be kept confidential. This keeps the rumor mill from getting started, and it helps to avoid the polarization that can take place when word gets around that a complaint has been filed.

If there are established internal procedures in place for handling discrimination and harassment complaints, such as those set forth in an employee handbook, employers must ensure that those procedures are followed to a T.

In harassment cases, prompt and appropriate remedial action must be taken if the complaint is substantiated. This is an absolute key to avoiding legal liability. If the investigation stalls or fails to result in appropriate remedial measures when harassment is proven, the employer will likely find itself in big trouble. The appropriate disciplinary response will depend on the nature and severity of the violation.

Employers cannot retaliate against employees because they complained about alleged discrimination or harassment.

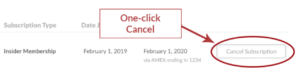

Some employees may choose to bypass the internal complaint procedure and go straight to the EEOC with an allegation of unlawful discrimination or harassment.

Employers that get hit with such a charge should begin by carefully reviewing the charge notice that the EEOC will send to them. This “Notice of a Charge of Discrimination” tells the employer that a complaint of discrimination has been filed against it. It’s important to note that this is merely a notice that a charge has been filed and that at this early stage of the case the agency has not yet determined whether the charge has any merit.

The notice typically will ask the employer to provide a response to the charge, also known as a “position statement.” This is essentially the vehicle by which the employer gets to tell its side of the story.

Even if the charge appears to the employer to be meritless, it’s imperative that the employer fully cooperates with the EEOC through the conclusion of the investigation, such as by complying with requests from the agency for additional information.

The EEOC typically offers mediation as a way to resolve the charge confidentially and swiftly. This can be a cost-efficient way to resolve the matter.

Here is more specific information on steps employers can take in the event they get hit with an EEOC charge.

EEOC Retaliation Guidance

The EEOC places a lot of emphasis on making sure employees feel free to complain about what they see as discrimination or harassment without fear of being punished by their employer for filing a complaint. That’s why the laws enforced by the agency ban retaliation.

Employees can’t be punished for complaining of discrimination or harassment, cooperating in an investigation or other proceeding, or filing a charge of discrimination or harassment.

Employers should remember that retaliation is a separate offense. In other words, an employer can be liable for unlawful retaliation even if the employee’s underlying complaint turns out to be meritless.

Example: Joe says co-worker Denise has been constantly subjecting him to unwanted sexual advances. Joe’s boss immediately demotes Joe before an internal investigation conclusively shows that Denise did nothing wrong. Joe does not have a valid harassment claim, but his odds of winning a retaliation claim against the employer are high.

To prove unlawful retaliation, an employee has to show that he participated in a protected activity; that he was subjected to a materially adverse job action, such as termination or demotion; and that there is a pretty clear causal connection between the protected activity and the adverse action.

In plain English: The employee must show he was punished for complaining or participating in a proceeding.

There are many things employers can do to reduce the chances that unlawful retaliation will occur in the workplace.

A simple and obvious step for employers to take is to have a clearly written, plain-language policy that specifically prohibits workplace retaliation. The EEOC recommends that employers include the following in the policy:

- Examples of prohibited acts of retaliation,

- Steps to take to avoid retaliation, such as guidance about supervisor and managers should deal with employees who have presented claims of discrimination

- A reporting mechanism, which simply means a way for employees to present allegations of retaliation, and

- A clear explanation that employees who retaliate can be disciplined.

Another tip from the EEOC: Get rid of any policies that might discourage employees from engaging in protected activities.

For example, a policy that imposes adverse actions on employees who discuss wages might constitute unlawful retaliation, the agency advises.

In addition to having a clear written anti-retaliation provision that is communicated to all employees, employers should keep in mind the crucial role that proper training can play in avoiding unlawful retaliation in the workplace.

Here are a few ideas for employers in that regard, courtesy of the EEOC:

- Provide anti-retaliation training, including refresher training, to all managers, supervisors and employees. Top management should make it clear that retaliation isn’t an option.

- Make sure employees know what is meant by “protected activity,” and give examples of how to avoid specific problem situations that might come up.

- If there has been an issue in the past regarding alleged retaliation, talk about how the situation might have been better handled.

- Let managers know that feelings of revenge or retribution may arise when an employee presents an allegation of discrimination – and that they cannot act on those feelings.

- Train managers and HR staffers on how to be both proactive and responsive when employees raise concerns about possible violations.

- Don’t limit training to office workers only. Instead, include all those working in a range of settings, such as manual laborers and farm workers.

- Generally encourage a respectful workplace.

Here’s another tip: If an employee files a complaint of discrimination, a built-in part of the employer’s response should be to tell all parties involved about the employer’s policy against retaliation.

It’s also a good idea for higher-ups to check in with involved parties, including supervisors and managers, while a discrimination investigation is pending to provide guidance and prevent unlawful retaliatory responses.

Finally, the EEOC advises employers to have someone review any proposed disciplinary measures to make sure they are not retaliatory in nature. The designated individual can be a management official or in-house counsel, the agency says.

Worth the read:

- EEOC’s New Retaliation Guidance Should Concern You: and Here’s Why

- EEOC Sees Retaliation Claims Rise: How to Stay Off Its Radar

- EEOC Drops New Guidelines on Avoiding Retaliation Claims

How to Prevent Harassment in the Workplace

Want to take the best path to preventing harassment in your workplace? Here are five core principles the EEOC says employers should keep in mind:

- Have engaged and committed leadership.

- Ensure accountability.

- Maintain strong and complete harassment policies.

- Make sure you have effective complaint procedures in place.

- Provide regular training that is tailored specifically to your organization.

Senior leaders must make the message loud and clear: Harassment at our workplace is not tolerated.

How do employers demonstrate this commitment?

One is for senior leaders to clearly and repeatedly make it known that harassment is prohibited.

Employers also need to make sure there are enough resources in place to enable the adoption and implementation of effective strategies that prevent harassment.

Assessment of risk factors is another important step toward preventing harassment, the EEOC says. Of course, when risks are identified steps should be taken to minimize or eliminate them.

A harassment policy should be comprehensive and easy to understand, and there should be a complaint system in place that all employees can readily access. Regular training is important, as are prompt and appropriate remedial disciplinary measures when they are warranted.

Worth the read:

- EEOC’s Latest, Best 10 Tactics for Preventing Harassment in the Workplace

- 3 EEOC Targets to Address in Your Harassment Training